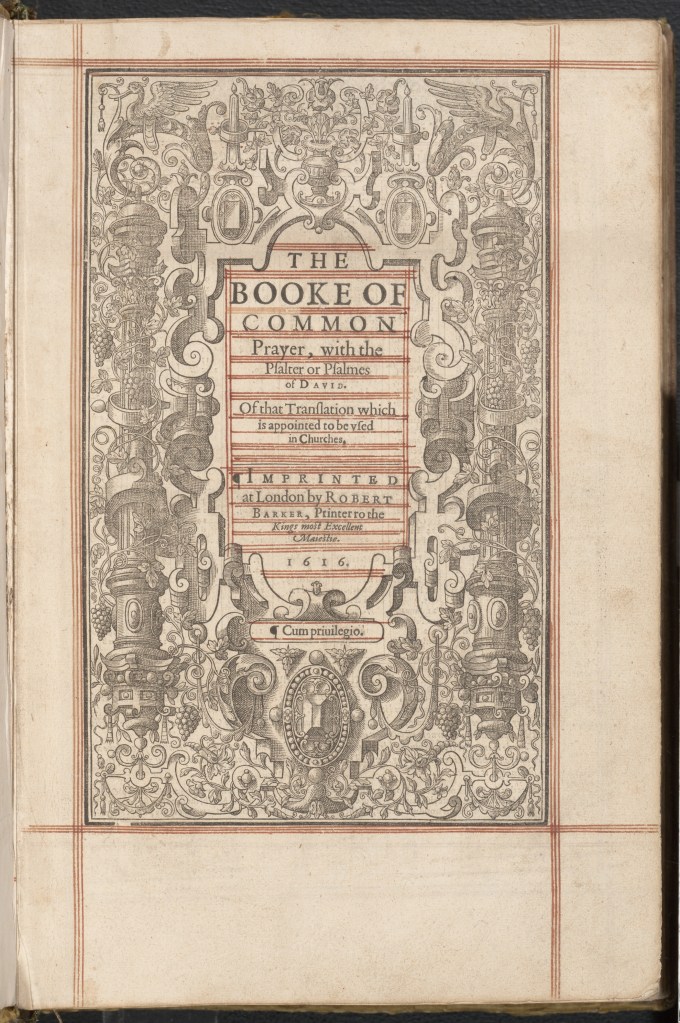

The English Prayer Book of 1549 introduced to the people of England a new daily Office. The monastic Breviary with its eight-fold daily Office (upon which pattern the Breviary recited, at least since the 11th century, by the secular clergy had been based) was no longer needed as a result of the Dissolution of the Monasteries. But Cranmer’s two-fold Office was by no means a complete innovation. Indeed, it went back to the pattern of daily worship in the first centuries of the Faith, when the Eucharist was celebrated on Sundays, and the people gathered for daily Morning and Evening Prayer – a non-Eucharistic celebration of psalms and Scripture reading.

It was this pattern of the Sunday Communion Service and daily Morning and Evening Prayer which Cranmer intended. (The later practise of celebrating the Communion Service on only four Sundays in the year, common right into the 19th century, is a lazy misunderstanding of Cranmer’s insistence that there always be lay people to receive Holy Communion with the priest – and the stubborn continuation of the laity of their pre-Reformation habit of receiving very infrequently!) The Prayer Book services are based on the earlier Offices of Lauds and Vespers, and their recitation was obligatory for all priests and deacons. But participation by the laity was encouraged by the rubric requiring that the parish priest recite the Office in church and ring the bell beforehand. The widespread neglect of the public daily Office by a section of the clergy of the Church of England from the 1950’s onwards and the substitution of a personal ‘Quiet Time’ certainly cannot be justified by any appeal to the Reformation liturgy of the C of E.

In the next century, in 1688, the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Sancroft, wrote to the Bishops of his Province urging the public performance of the daily office ‘in all market and other great towns’. In 1714 a large proportion of London churches had daily Morning and Evening Prayer, with the morning Office sometimes as early as 6am. The departure of the Non-Jurors, the so-called ‘Glorious Revolution’, and the arrival of the Hanoverians, combined to rob the Church of England of a disciplined spiritual life, and the Evangelical Revival concentrated principally on personal devotion.

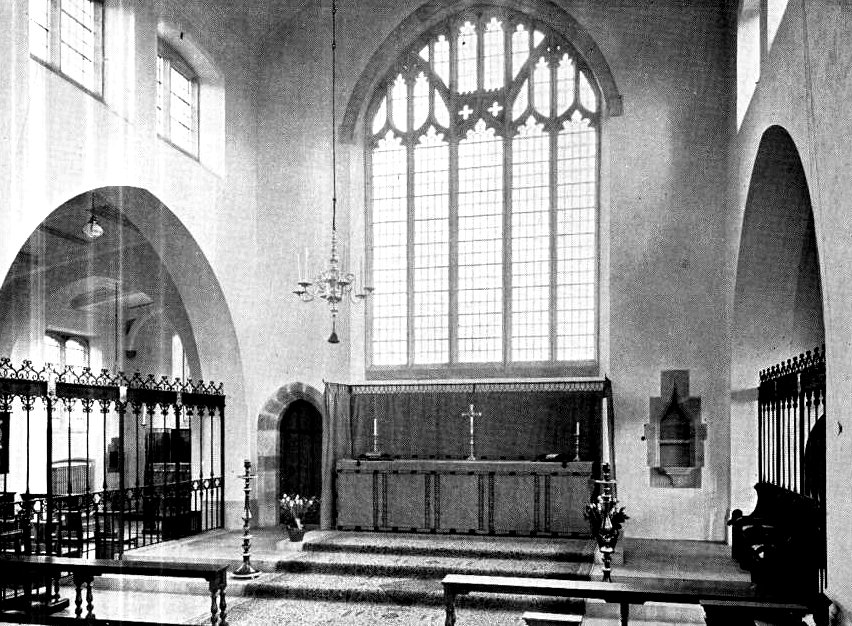

The Oxford Movement sought to restore obedience to the Prayer Book together with renewed emphasis on the spiritual life of the clergy. The recitation of the Offices of Morning and Evening Prayer in the Parish Church was high on their list of priorities.

But the restoration of the Religious Life, first for women and then later for men, led to difficulties concerning the Office. In the contemporary (Roman) Catholic communities there was a strict division between those orders, monks and nuns, who recited the whole monastic Daily Office from Matins to Compline, in choir, and Religious, active in the world, who recited a much shorter and limited daily round of prayer. For Anglican Communities English translations of the Office with plainchant adapted so that the Offices could be sung, soon appeared. These translations were often based on English mediaeval uses (Sarum in particular) so as to appear rather more loyal! The number of communities using the Roman Office in Latin was always small, the Benedictines of Nashdom being perhaps the best-known.

Equally small was the number of Anglican clergy who recited the Latin Breviary in place of the Prayer Book Offices, although more would have supplemented with the minor Offices taken from the ‘Day Hours’. The appearance of the Liturgy of the Hours in 1971, in Latin and then in an authorised English translation (as is usual in Catholic liturgical books) brought about a remarkable change in the liturgical life of the clergy of the Church of England. Almost unanimously (among the Anglo-Catholics) they switched to this new five-fold Office.

It is important to remember at this point the different attitude to the Book of Common Prayer and the use of modern English, a difference in understanding and approach between ‘traditionalists’ in the Church of England and the Episcopal Church in the USA. It was a difference which was to be fundamental, I believe, in the creation of the various Ordinariate liturgies. For most ‘traditionalist’ Anglo-Catholics the Book of Common Prayer was a Protestant manual which had been imposed upon the English Church by the monarch and Parliament. They may have retained an affection for ‘Choral Evensong, but by and large were glad to see the Prayer Book eclipsed by the modern language services – though disappointed by the concessions made over evangelical shibboleths like the word “offer” in the Eucharist and prayer for the dead in the Funeral Services. The Americans traditionalists came to believe that the Prayer Book (in thee/thou language) represented catholic orthodoxy, and they associated modern language with the liberalism which was then sweeping through the Episcopal Church. (Ironically, there was even a sense among English Anglo-Catholics that those who clung to the ‘old services’ presented with ceremonies abolished after Vatican 2 were ‘High Church’ rather than ‘Catholic’!)

And now brief diversion into the changes in the Office which were being piloted in the Religious Communities of the Church of England int he 1970’s – it was, after all, they who had deeply influenced liturgical development in the 19th century. Two examples will have to suffice …

The reforms to the (Roman) Catholic Mass had introduced a new lectionary of scripture readings. Over the course of 3 years on Sundays, and 2 years on weekdays, all of the New Testament, and much of the Old Testament was to be read in course. But this left a problem for Anglicans who already had a Daily Office lectionary giving them four readings a day. The Kelham Fathers (the Society of the Sacred Mission – SSM) in their new liturgy of 1970 composed a daily lectionary of six readings – Old Testament, New Testament and Gospel – to be read, three in the morning and three in the evening. The morning liturgy combined Morning Prayer with the Liturgy of the Word, with the psalms and canticles recited between the readings. This pattern could also be observed when the Mass was celebrated in the evening as on Maundy Thursday. It worked less well on Feast Days with a Midday Mass – when the form of Midday Prayer was recited first thing in the morning! The ceremonial was pushed to a curious – though logical, I suppose – conclusion at Solemn Evensong on Sunday. No longer was the altar censed at Magnificat but a procession formed to the lectern for the reading by the Officiant of the Gospel.

A rather different pattern was evolved by the Franciscans (the Society of St Francis – SSF) whose Office I personally used in the 1980’s. (I had stopped using the Roman Divine Office when I became an incumbent and welcomed a curate from St John’s College, Nottingham! The little brown book provided a four-fold office with Morning and Evening Prayer based on the Prayer Book form. There was a lectionary, psalter (the Revised Psalter, I think) antiphons for Benedictus and Magnificat, full provision for Solemnities like the Assumption – but one needed a Bible for the readings. (Exactly the right size was the Good News Bible TEV – a terrible translation but I liked it for its freshness and vigour.) The Franciscans went on to develop a form which eventually found its way into Common Worship though in a form, if I remember correctly, which was disowned by the Franciscan liturgists. Correct me, someone, if I have got it wrong.

The developments in the history of the Anglican Office have found their way into the Catholic Church with the publication of the Divine Worship Daily Office. Interestingly, this is the “Commonwealth Edition” meaning, one imagines, for the use of the UK and Australian Ordinariates. What then of the United States, which had so much influence on the Divine Worship Missal?

But the question of modern or traditional la nguage hardly seems important to me, though I am aware that for some the language of Cranmer, and the 19th century attempts to write in it in the various Missals, are a part of the Patrimony. More interesting, it seems to me is (1) whether the public recitation of the Office can exist alongside the Catholic tradition of the Daily Mass. (This was not an issue for Cranmer, and the Oxford revival of frequent celebration of the Eucharist would seem to suggest that it cannot) and (2) can Cranmer’s vision of the laity responding to the bell of their parish church and joining their parish priest in reciting the Daily Office be realised in the very different conditions of the 21st century?

On the other hand, the shortage of priests and electronic ways of group meeting, like SKYPE, have suggested to one of my friends, a rather different way of developing the daily Prayer of the Church. Hmm.