In my last year as a parish priest in France I was twice asked to preside over funerals where the cremation of the body had already taken place. No funeral directors attended, and the family arrived with the urn or casket. I consulted the diocesan responsable, who sent me the relevant directions and guidelines. Most significantly, there was to be no censing and sprinkling of the urn or casket, and no Bénédiction du corps, the noteworthy (and often lengthy) ceremony where the whole congregation files round the coffin, sprinkling, and often nowadays touching and kissing it. The reason given for this denial is that there is a significant difference between the body of the departed person, brought into church for the funeral liturgy preceding burial or cremation – and the ashes which are the end result of the disposal of that body – many years of decay in the case of burial, and a much shorter and accelerated process in the case of cremation.

Coming back in retirement to the UK I confess to having seen rather a lot of day-time television. There are a huge number of advertisements for funeral plans and especially for ‘direct cremation.’ The high cost of funerals is alluded to but the advertisements are full of cheerful reasons for this sort of funeral: it is more personal and allows the family to organise the ‘service’ they want (or imagine that the departed person would have wanted) which now takes place without the body and presumably some days, weeks or even months after the death. So the process now becomes: death of the person concerned – collection of the body which is taken without ceremony to the crematorium; without prayer or committal the body is cremated and the ashes returned to the family. The saving in time for the funeral directors and the crematorium are enormous and indeed, it is a wonder that the average cost of such a ‘direct cremation’ is as high as it is – up to 50% of a ‘traditional’ funeral.

I was a parish priest in East London in the 1980’s and among the older generation a “good send-off” was important. Many families still had the body brought home before the funeral. The funeral directors would usually contact the parish clergy and expect them to visit, to meet the family and plan the service. In Canning Town the departure from the house was an important moment with neighbours lining the street and curtains drawn. The funeral directors were mainly local, independent firms who may well have served a family on several occasions, and through several generations. Where a trusting relationship existed between the priest and the local FD’s much good was done, and the pastoral relationship between the vicar and his parishioners cemented and renewed. (You must remember that I am talking of my Anglican days – I suppose that the situation was different for Catholics with a clearer sense of identity than those who said ‘C of E I suppose’ in response to any question about their religion!)

In the decades that followed these traditional funeral practises changed. The smaller firms of undertakers were bought out by bigger (sometimes American) companies. They had little understanding or time for the concerns of the clergy. They wanted a ‘celebrant’ who would be easily contactable and ready to do and say what they imagined the family wanted to hear. These large firms quickly started to behave as if the ‘celebrant’ was employed by them. We are not talking about ‘secular’ or ‘civil’ funerals (a distinction which is clear in France) and indeed, I once saw an advert for this type of funeral which included the option of ‘a bit of religion’ (Psalm 23 or ‘The Lord’s Prayer’?)

Odd as it may seem, funeral services became longer in the search to make them more ‘personal’; 15 minutes at the Crematorium was the norm in the 80’s. As the younger generation lost even the rudimentary Christian Faith of their parents and grand-parents so the content of funeral services changed. The reading of scripture was replaced by sentimental poetry; prayers for the departed were replaced by assertions that ‘she will live forever in our hearts’; and notions of judgment and forgiveness were banished from the ‘Celebration of Life’ of those who had not died, but rather ‘passed away’. Pictures and videos of the dead person as they had been before old-age, decline and dementia, took their toll, replaced the coffin as the centre-piece of these new ‘services’ with mourners ditching black in favour of bright colours for, of course, he ‘wouldn’t want us to be sad’.

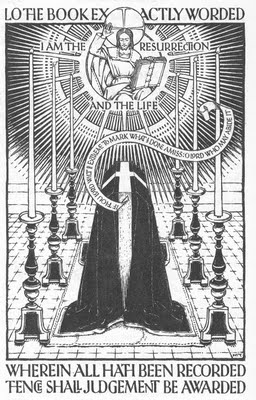

Now I don’t deny that the Church – clergy and laity – have played their part in this baleful process. Some clergy have preferred administration to the care of the dying and bereaved; the Evangelicals in the C of E with their outdated fears of ‘Prayer for the Dead’; and the laity with their uncertain witness to the hope of Resurrection (and mouthing phrases like ‘she’s gone to a better place’) . But where has this process taken us. I reflect that the Christian Church is excluded from advertising. Yet the funeral companies are allowed to spend fortunes on persuading the British public to shy away from the fact of death and the pain of bereavement. The Christian Faith and the practises which surround both death and bereavement are not there primarily to comfort – and certainly not to suppress the profound grief experienced at the death of those whom we have loved – but to acknowledge the awesome reality, to take us through the long process of loss, and to proclaim the Good News that Jesus Christ has conquered Death – the Last Enemy.