“And as they were eating, (Jesus) took bread, and blessed, and broke it, and gave it to them, and said, “Take; this is my body.” (Mark 14:22 RSV)”

“And as they were eating, (Jesus) took bread, and blessed, and broke it, and gave it to them, and said, “Take; this is my body.” (Mark 14:22 RSV)”

Read the words in black: do the words in red.” However inadequate that might be as a direction to the priest celebrating the Mass, it will do nicely to begin reflecting on what Anglicans might bring with them of their liturgical history and experience, as they enter into full communion with the Catholic Church through the Ordinariate. Words and actions, rite and ceremony, text and rubric …

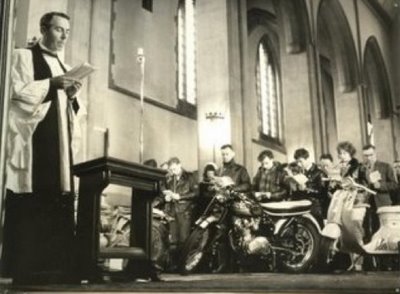

God created human beings for worship, above everything else. When we worship God we are at our truest, and when we do not worship we are lost, lonely and unhappy. This is what lies behind the Church’s insistence that we ‘go to Mass on Sunday’. The first Christians did not need telling, for we read, “And day by day, attending the temple together and breaking bread in their homes, they partook of food with glad and generous hearts, praising God and having favour with all the people. And the Lord added to their number day by day those who were being saved. ” (Acts 2:46-47 RSV)

Notice that the last sentence, which tells us that the growth of the early Church followed immediately on from its worship, and the attitude of the first Christians to it. When the Church praises God with glad and generous hearts, people come to faith in Christ and the Church grows. In the words of the Anglican liturgy from the Preface of the Eucharistic Prayer: “It is not only right, it is our duty and our joy.” As Anglicans we often envied the dutiful way in which our Catholic brothers and sisters made Sunday Mass their obligation; we want to graft on to that duty our deep sense of celebration, in going to Mass because it is our joy to do so!

The beauty of the liturgy

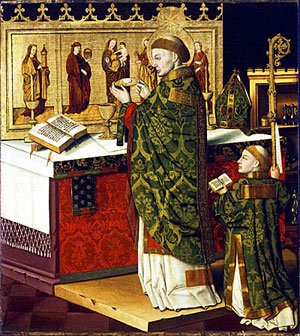

We need just to make this point: that correct liturgy is not necessarily good liturgy. But good liturgy will always be beautiful liturgy. This applies whether we are worshipping with all the grandeur and resources of a cathedral, or celebrating Mass in a caravan on a children’s holiday. Much of the responsibility for this will fall on the priest who is presiding, to make the liturgy glorious, wherever he is. It is not enough for him simply to know how to do the words in red. He must have a profound personal faith in God, a deep concern for the people over whom he presides, and a self-effacing humility which enables him to give away to others their part, equally with him, in the celebration. Much of this comes with time and experience, and it takes years of practise and prayer. To take part in the Mass celebrated by one who has been a priest all his life, to see the quiet devotion, the unhurried care with which every action is done and every word spoken, this is a real joy.

The beauty of the liturgy is not easy to define. We live in an age of relativism, and we are quite used to hearing people talk about what is true ‘for them’. We have become convinced that beauty is a ‘matter of opinion’, and so we divide into groups based on ‘what I like’; we avoid the difficult arguments which look for principles. As Anglicans we lived with a certain liturgical anarchy, and the adage that ‘every priest was a pope in his own parish’ was nowhere more true than in the liturgical practices which, too often, depended on ‘what Father likes’. My own impression was that many serious minded (Anglo) Catholic clergy adopted the 1970 missal as a mission principle – because it saved them from hours spent compiling ‘services’ and arguments with servers about who should be censed at the offertory! But if it is not easy to define the principle of beauty – in liturgy or anywhere else in life – then we must at least try.

Percy Dearmer, the great protagonist of the English Use of the Prayer Book is as forceful as he always was:

Vulgarity is … due to a failure to recognize the principle of authority; and authority is as necessary in art as it is in religion. Every one does what is right in his own eyes, because we have refused to accept the first principles of the matter, the necessity of wholesome tradition on the one hand and of due deference to the artist’s judgement on the other. We do not listen to the artist when he tells us about art, and we are surprised that he does not listen to us when we tell him about religion .. Most of the tawdry stupidity of our churches is due to the decline of art in our more recent days. The Parson’s Handbook, 8th edition, 1913

Liturgical renewal flowing from the Second Vatican Council

The reform of the liturgy was one of the major works of the Second Vatican Council. At first it seemed that the Novus Ordo of 1970 would simply replace the ‘Tridentine’ Missal promulgated by Pope Pius V in 1570, as that Missal had replaced the various national and diocesan variants of the Middle Ages. Such was not the case, and the arguments of recent years between ‘traditionalists’ and ‘modernisers’ are not nearly so clearly defined as the extremists on both side would like to have it. It is common, but wrong, to refer to the ‘Tridentine’ Missal, as the ‘Latin Mass’. The 1970 Missal of Pope Paul VI was composed in Latin and translated into the vernaculars: in England we now have a new English translation, which we have been getting used to since Advent 2011. But the current Missal (the Ordinary Form of Mass) may just as well be celebrated in Latin as in English. Indeed, in my own Catholic parish the 11.15 Mass on Sunday is entirely in Latin (except for the readings, homily and intercessions) with the large congregation joining in lustily in the singing of gloria and creed to Missa de Angelis. And the ceremonial is that of the 1970 Missal: the celebrant faces the people at the altar, he presides from the chair for the Liturgy of the word, readings are from the ambo. I’ve laboured this point perhaps. But it is quite wrong to associate in people’s minds the 1970 missal with ‘guitars and crimplene vestments’. I speak of my experience while in the Church of England, where those Anglo-Catholic parishes which used the Roman Missal often did so with the ‘noble simplicity’

we ought to associate with the celebration of the Mass, in whatever form it is celebrated.

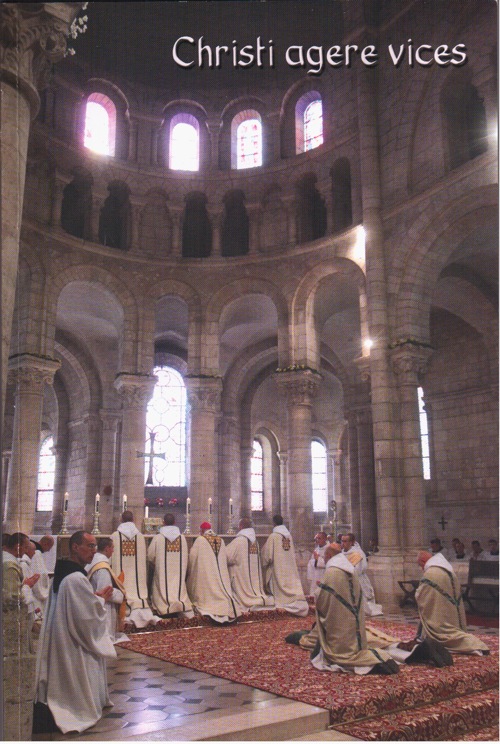

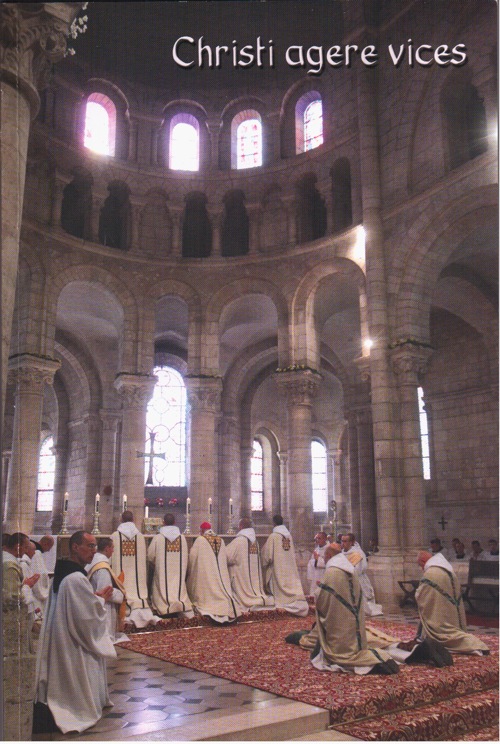

My exploration of France took me, some years ago, to the Abbey of Fontgombault, where the monastic community uses the latin Office and the 1962 missal. There are some interesting pictures of the liturgy on the New Liturgical Movement website, where the full vestments, flowing surplices and the long altar with its low candlesticks would warm the heart of any ‘English’ enthusiast, surely.

The renewal of worship and the Anglican experience

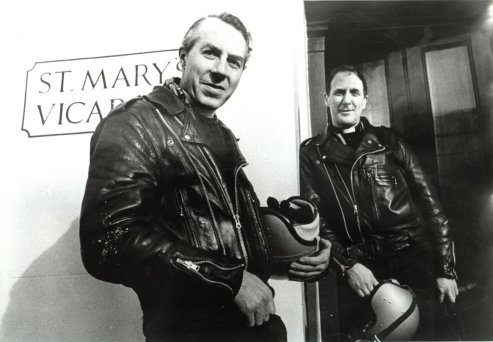

Students for the Anglican priesthood at Kelham received in their final year training in the celebration of the Eucharist. This was less to do with the following of rubrics (it was expected that your training incumbent would do this while you were still a deacon) but much more about deportment (how to move slowly, gracefully and yet in a manly way), voice production (clear, calm, avoiding the extremes of the bored gabble on one hand, and the ‘full of meaning’ voice on the other) wearing the vestments properly (no knee-length albs ever permitted at Kelham) and a host of other preliminaries which the priest needs to learn before he even leaves the sacristy.

These things we prided ourselves on as Anglicans: and when we got it right our worship was profoundly beautiful. Of course, these things do not in themelves make for authentic worship for that is a gift of God to those whose hearts are open to receive it.

Now with the Christian altar comes a new focal point. Let us say it again: on the altar what the Temple had in the past foreshadowed is now present in a new way. Yes, it enables us to become the contemporaries of the Sacrifice of the Logos. Thus it brings heaven into the community assembled on earth, or rather it takes that community beyond itself into the communion of saints of all time and places. We might put it this way: the altar is the place where heaven is opened up. It does not close off the church, but opens it up – and leads it into the eternal liturgy.

The Spirit of the Liturgy – Pope Benedict XVI p.71