Thaxted Church in Essex

At the Reformation the Catholic Mass emerged from behind the screen and became visible: the Anglican liturgy emerged from behind the screen and became audible.

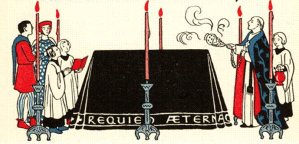

Compare and contrast, as they used to say in exam papers, the mediaeval building with its long chancel and rood screen, with the classical churches of Rome or the baroque churches of Austria. In the former the liturgy is veiled and distant, the people are almost in another room. In the latter the altar is visible, close, and all the participants are in a single space. In the Anglican buildings from the 16th – 19th century it is the pulpit which dominates often with the reading desk. The word is proclaimed to the people in their pews. From time to time – even every Sunday in town churches – some will move from their seats to gather round the Holy Table. The action of the liturgy, which had almost disappeared in the 1552 Prayer Book of Edward VI, is somewhat restored in the 1662 Book where the priest is required to place bread and wine on the Table, and during the Prayer which is now headed Prayer of Consecration, he is to take the bread and break it, and then to take the cup of wine. In the Catholic Mass of the post-Reformation period there is considerable (perhaps too much) action, but at the heart of the liturgy the taking-blessing-breaking-giving action remains intact. The gradual withdrawal of the laity from Communion, which began in the mediaeval period, has now become the norm. It takes the concerted action of Pope St Pius X at the beginning of the 20th century to restore this central act of participation to the Mass.

The Gothic Revival in architecture in the 19th century, combined with the Oxford Movement in the C of E, saw the restoration of the altar, though distanced from the people by the erection of screens and the positioning of the robed choir in the chancel. In spite of the frenetic activity of AWN Pugin, the long chancel and the screen did not return to Catholic worship: indeed, the colossal reredoses and soaring Benediction thrones serve to make the sanctuary more prominent, though sometimes reducing the altar to the appearance of a shelf or sideboard.

The Gothic Revival in architecture in the 19th century, combined with the Oxford Movement in the C of E, saw the restoration of the altar, though distanced from the people by the erection of screens and the positioning of the robed choir in the chancel. In spite of the frenetic activity of AWN Pugin, the long chancel and the screen did not return to Catholic worship: indeed, the colossal reredoses and soaring Benediction thrones serve to make the sanctuary more prominent, though sometimes reducing the altar to the appearance of a shelf or sideboard.

So we enter the 20th century with the Liturgical Movement in both the Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion, encouraging the restoration of both the visual and the aural, action and word, in the worship of the Eucharist. This is realised to some extent in the Parish Communion Movement in the C of E, though there is a reactionary movement among some Anglo-Catholics copying the then current Catholic practice, and among Evangelical Anglicans who want to return to a Cranmerian doctrine of the Communion Service, and for whom action leads inexorably to offering.

In the liturgical reforms which emanate from the Council, the restored emphasis is on both action and word and the full participation of the whole People of God in the worthy offering of the Mass.

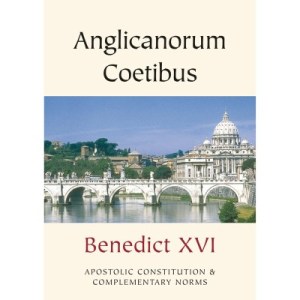

The Ordinariate liturgy stands within the liturgical and theological context of the Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite. In its celebration therefore, the active participation of all the people is to be clearly seen. From the theological emphasis of the English Reformation comes its insistence on the proclamation and preaching of the Word of God in scripture.

The Ordinariate liturgy stands within the liturgical and theological context of the Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite. In its celebration therefore, the active participation of all the people is to be clearly seen. From the theological emphasis of the English Reformation comes its insistence on the proclamation and preaching of the Word of God in scripture.

Fr Herbert McCabe, writing in 1964, said, “The actual Scriptures ceased to be thought of as a nourishment for Catholics, and they substituted books of Christian doctrine. It did not seem to them scandalous or even particularly surprising that the Epistle and Gospel at Mass should be read in an inaudible manner in a foreign language by someone standing with his back to them – it is all right because soon he will turn round and tell us quite audibly about the catechism and the second collection. ” (The New Creation – Herbert McCabe OP p.14)

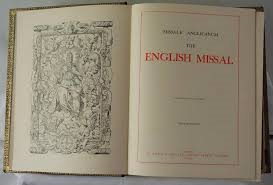

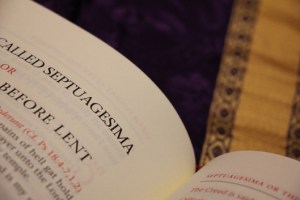

The ‘proclamation’ of the Ordinariate liturgy in a careful, articulate, thoughtful and coherent manner is all the more important because it uses Tudor English, with words and grammar which are not immediately obvious to our generation. Speaking too quickly, mumbling, emphasis on the wrong words all detract from the one of the fundamental principles of the liturgical patrimony of Anglicanism, clearly included and incorporated in Divine Worship.

It will not be easy, that is clear. We live in an age when the English language, because of its wide use across the world, is subject to uncontrolled change. Unlike the French, we have no Académie to direct the evolution of the language. To suggest that some new words, phrases and grammatical constructions have debased and spoiled the language are greeted with hoots of laughter and cries of ‘elitism’. The truth is worse still: that many of these words and phrases are designed to hide the real meaning or to cover up the fact that the speaker does not know what he is talking about!

Divine Worship is not perfect. It includes ‘sublime’ Cranmer (the Collect for Advent Sunday), ‘heavy’ Cranmer (the Confession at Mass) and sometimes the sort of latinate translations so wickedly parodied by Fr Harry Williams CR in his autobiography. But nonetheless, when it is used it deserves to be ‘proclaimed’, as far as the words of the liturgy are concerned, with clarity, simplicity and even a certain elegance; but always with the intention that it shall be ‘Pastoral Liturgy” – that the people may be enabled to worship worthily and to grow in the faith.

Last year I celebrated the liturgies of the Easter Triduum on my own! We were in lockdown, here in France. This year we are in lockdown again, but we can gather in church for worship providing we are careful to observe the necessary precautions. But one of features of the confinement is the curfew: we cannot go out after 7pm. This meant no Vigil during the night of Holy Saturday, and we were advised to celebrate it beginning before dawn on Easter morning.

Last year I celebrated the liturgies of the Easter Triduum on my own! We were in lockdown, here in France. This year we are in lockdown again, but we can gather in church for worship providing we are careful to observe the necessary precautions. But one of features of the confinement is the curfew: we cannot go out after 7pm. This meant no Vigil during the night of Holy Saturday, and we were advised to celebrate it beginning before dawn on Easter morning.