Between the end of the 19th century until the 1970’s English music enjoyed a period of greatness perhaps not seen since the time of Purcell, maybe even since the flowering of English music under the Tudors. Composers such as Elgar, Parry and Stanford, Vaughan Williams, Gustav Holst, Ethel Smythe, Gerald Finzi, Eric Coates and William Walton, reached deep into the long heritage of English music. They brought forth music which was fresh and innovative yet rooted in the tradition: music which was evolutionary not revolutionary.

Rooted in the tradition because they had been part of the revival of folk music, the music of generations who sang and played instruments. These were ordinary people who, before the invention of the record, CD and music-streaming, ‘made music’ for every sort of gathering. The folk songs are simple without being banal, and memorable without being trite or boring. They are melodious and expressive of joy and sadness – indeed of all the emotions and occasions of human life.

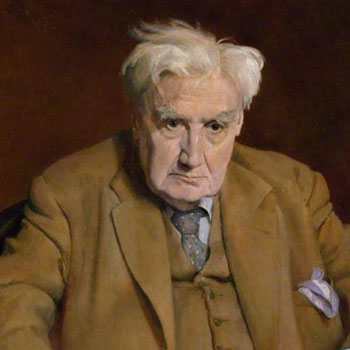

In rediscovering this deep-rooted tradition of music our English composers added elements like superb orchestration which was original and capable of carrying deep emotion. (A good example might be in the contrast between Elgar’s ‘Pomp and Circumstance Marches’ and the ‘Cello Concerto). Some of the music is exquisitely beautiful (‘The lark ascending’ by Ralph Vaughan Willams) without being in the least ‘saccharine’. Much of it is popular and accessible – ‘The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra’ by Benjamin Britten, or the war-time music of Eric Coates and his ‘The three Elizabeths’ Suite.

After the Second World War popular music took a new turn in looking towards America for inspiration. A whole genre of music, at first called ‘Rock and Roll’ flooded into the UK, assiduously marketed by the promoters who saw money to be made from a generation of young people now called ‘youth’. Exploiting their desire to distance themselves from their parent’s generation, the ‘music industry’ characterised all earlier music as ‘boring’ and lacking in ‘cool’. Classical music in reaction became increasingly experimental and inaccessible to many people: although rejecting cries of ‘elitism’ it became more and more elitist!

- * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

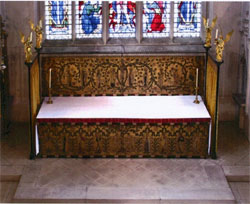

The same period was one of growth and development within the Church of England of a peculiarly ‘English’ style in the ordering of its worship. Increasingly conscious of its Catholic roots the movement reached behind the controversies of the Reformation to the mediaeval period. The beautiful creations of Ninian Comper (the ‘English altar’ at Cantley and the church of St Cyprian, Clarence Gate in London) in his early period are typical examples.

During this period many English Cathedrals were re-ordered, and the heavy Victorian Gothic Revival furnishings removed. Side chapels were re-instated, nearly always with ‘English’ altars. The total effect was fresh and lively with colour, due to the fashion for whitewashed interiors. This was hardly mediaeval, for the churches of that era would have been painted and decorated all over. One gets some idea of the original effect from St Giles’ Cheadle (by AWN Pugin) or Comper’s Crypt Chapel at St Mary Paddington. Yet the instinct was a right one – and the effect of a large, well-lit church, like the parish church at Thaxted, its spacious white interior cleared of pews, its shrines, altars and flower displays creating splashes of colour, is spectacular. If the early designs of Comper, rich and luxuriant, evoke the music if Elgar and Parry, then perhaps the church at Thaxted brings to mind Vaughan Williams – or indeed, Gustav Holst who was musical director there!

The church built at Mill Hill to honour the saintly John Keeble, instigator of the Oxford Movement (the 19th century Catholic Revival in the C of E) shows that this ‘English’ Movement was no pseudo-mediaevalism. The same elements are there: the white interior, the long High Altar (as originally built the altar was longer and surrounded in three sides by curtains, the east window coming down to within a matter of a few feet of the altar, the splashes of colour at the altar and ambos. Liturgical renewal has clearly affected the design, for the church is wider than it is long, there are no pillars, and the choir of singers is placed in the midst of the congregation. In the 1960’s, as I can testify, the Parish Eucharist was both serenely beautiful celebrated with three sacred ministers, and with full participation by a lively and welcoming congregation.

Sir Ninian Comper began to question his earlier assumptions about church planning. His researches in North Africa led him to develop a much more open plan with the altar separated from the nave only by low rails, and the congregation able to gather around the sanctuary. His theory of unity-by-inclusion enabled him to draw together design elements from classical and gothic architecture. The photograph of St Philip’s Cosham in Hampshire shows a church, totally in line with current liturgical thinking, glowing with colour especially around the altar which is the heart of the building, and drawing on a building tradition 2,000 years old. A remarkable achievement! And one which is surely in line with the musical developments – drawing on a long tradition to evolve and grow – of this fascinating period.

A trip down memory lane to a period now almost beyond living memory? Or a source of inspiration for a generation just beginning to understand the importance of beauty and tradition in worship – and indeed all of life. An English tradition surely dear to the hearts of Catholic Christians in the Ordinariates? A guide perhaps for those clergy and laity (with limited numbers and money) wondering what on earth to do with their grim concrete box of a church built in the 1960’s, asking themselves whether it can ever be beautiful, welcoming and worthy of the worship of heaven celebrated in the Mass?