The annual trip to London was much looked forward to by us teenage servers. It was organised by the Guild of the Servants of the Sanctuary, and involved servers, wives, children and several clergy piling into a coach and heading off to the capital. I suspect that the wives went off shopping and sightseeing (a trip to London was still quite an event even in the 1960’s) while we servers went to the annual Easter Saturday (the Saturday after Easter, of course) High Mass at St Augustine, Queen’s Gate. I freely admit that it was very bad for me, as for several of my teenage compatriots, and our Vicar must have dreaded our return. For it was here that we saw the latest (as we imagined) London fashions in liturgy: lace albs (the celebrant’s lifted by the deacon and subdeacon as they went up the altar steps) communion from the tabernacle, birettas and servers with the tiniest cottas trimmed with crocheted lace. Mercifully, the Vicar took no notice of the servers’ pleas to ‘do things properly, Father’ , for the worship of the Anglo-Catholic parishes in the provinces was already overtaking that in London. The once great shrines were falling behind as the movement for the Parish Mass took hold of Anglo-Catholicism, and became, perhaps, its most lasting liturgical achievement. Indeed, I would want to argue that it is one of the most important contributions which the Ordinariate brings to the renewal of Sunday worship of the Catholic Church.

Peter Anson, in ‘Fashions in Church Furnishings’ points to a curious anomaly. The ‘Back to Baroque’ Movement in the 1920’s, which transformed a number of English parish churches into quite passable replicas of their French and Belgian counterparts, was happening at the same time as the Liturgical Movement was gaining ground in the Catholic Church on the Continent. I had (before I culled my library on retirement) the privately published memoirs of Fr Merritt, who had been Vicar of a parish in West London before the Second World War. He writes of his great achievement by his third Easter there, when there were something like 750 communions at the 6am, 7am and 8 am Masses, but only one (himself as the celebrant ) at the High Mass at 11 am. Yet at precisely this time, liturgical scholars were pointing to the Eucharistic doctrine and practice of the early centuries, and asking whether a return to the Sunday gathering of the whole congregation, with general communion, was both possible and desirable.

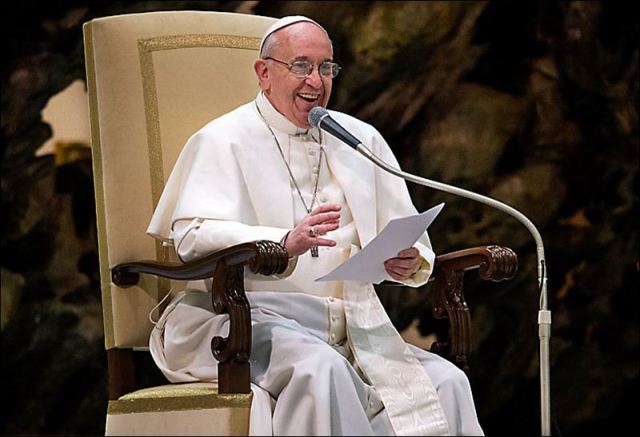

The Movement had found inspiration in the immense shift in Catholic devotion under Pope St Pius X. Remarkably he had overturned the practice of centuries, by which many Catholics only went to Communion at Easter. Frequent, even daily, communion became in the 20th century, common again. Then, during the Second World War, Pope Pius XII realised that many Catholics were unable to go to Communion because of war-time conditions. So he relaxed the fasting rules and permitted Evening Masses.

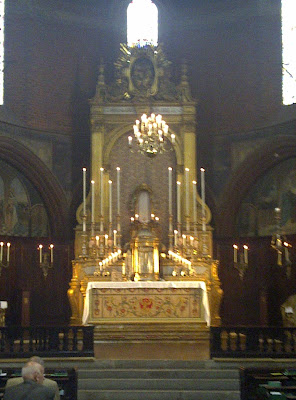

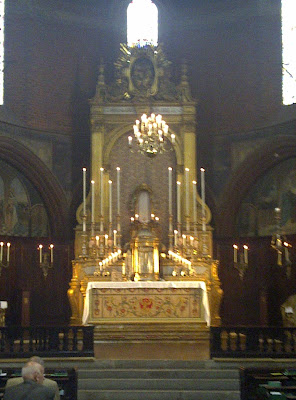

The Christian altar

The growth of the Parish Mass movement in the C of E was coming from a very different direction. After the break with Rome in the 16th century, Archbishop Cranmer produced an English Prayer Book. As he revised it in 1549 and 1552 its theology reflected the Archbishop’s own move away from orthodox belief about the Eucharist towards ever more extreme Protestant views. However, it would appear that he envisaged his Communion service as central to Sunday morning, for it is the only service at which a Sermon is ordered. In an attempt to get the laity to go to Communion more frequently, he outlawed non-communicating attendance. But the laity refused to budge, with the unforseen result that the clergy were unable to proceed with the Communion Service, ending it after what we now call the Liturgy of the Word. The established pattern of worship thus became Morning Prayer, the Litany and Ante-Communion. Four times a year (but more often in town parishes) the Vicar then led the more devout into the chancel and there proceeded with the second half of the Communion Service.

The Oxford Movement (or Catholic Revival) beginning in 1833 led to the rapid introduction of weekly (and even daily) celebrations of the Eucharist. A Sunday celebration at 8 am became the norm. At first this was followed by Morning Prayer, usually sung by the choir at around 11 am and Evening Prayer later in the day. With the second generation of the Revival, often known as the ‘Ritualists’ a Sung or Choral celebration displaced Morning Prayer. Strict notions of preparation and fasting from midnight made the reception of Communion at the Sung Celebration difficult. Protestant anger was aroused by these ‘non-communicating’ services, since it was obvious that the people came to adore the Eucharist rather than to communicate! Two patterns of Sunday morning worship in the Church of England developed. Country parishes of a more moderate churchmanship, and eventually even the Evangelicals, adopted a weekly early Communion, followed by Morning Prayer at around 11 am. As the Catholic Revival grew in its ascendancy more and more churches introduced a Sung celebration with Morning Prayer said earlier.

All of this is in marked contrast to the pattern in the (Roman) Catholic parishes of England. The mainly urban, working class parishes had huge numbers to pack into far fewer church buildings. Not having the Established Church’s inherited money, it relied on large but unpretentious buildings being full five, six or more times on Sunday. High Mass with its ministers and elaborate ceremonial was virtually unknown. The 11 am Mass might have a small choir to sing two or three well-known hymns. Put crudely the emphasis might be characterised as ‘hearing Mass’ rather than ‘making my Communion’.

Two Anglican Religious were responsible for giving the intellectual and theological rationale for the Parish Mass: Dom Gregory Dix OSB in The Shape of the Liturgy, and Fr Gabriel Hebert SSM in The Parish Communion. The books helped to drive forward the growing desire to restore the Sunday Eucharist to the central position on Sunday, and to ensure that priest, ministers and people participated appropriately, but fully and intelligently – as they believed, had the Christians of the first centuries. Anglicans were rather freer than Catholics to experiment liturgically, as they already had a vernacular liturgy. The Anglo-Catholics had pushed the recovery of something rather more like the order of the primitive Eucharist, in the face of conservative Protestant clinging to the Prayer Book rite. From the 1950’s onwards more and more Church of England parishes were to introduce the Parish Eucharist as the main service, usually at 9 or 9.30 am so as to allow people to come fasting. Indeed, breakfast was often provided afterwards and enabled the congregation further to develop that sense of Christian community which they had celebrated in their worship.

eventually, even the Evangelicals began to move with some introducing the Parish Communion while retaining Morning Prayer at the sacred hour of 11 am. But this change was not to last, and as their ascendancy grew (and Catholic influence waned) so their innate suspicion of the Eucharist (and of the sacramental principle as a whole) led them into ‘Family Worship’ which bore little resemblance either to the practice of the early Church, or to the classic formularies of Anglican worship.

Much of what the Liturgical Movement had pioneered was triumphantly acclaimed in the reforms which followed from the Vatican Council. Many Anglicans believed that with the Mass now celebrated in the language of the people, with altars looking rather more like tables and less like sideboards, and with vestments modelled on the cloak left by St Paul at Troas (at least in the minds of some of the very creative liturgists) the Anglican reform had now been vindicated. But Anglo-Catholics began to suspect that the enthusiasm of many liberal Anglicans was only skin-deep. Behind the Parish Communion lay a very hazy grasp of what the Eucharist actually was. Indeed, in one parish magazine the Vicar wrote. ‘The Communion Service is really very simple: we eat bread and drink wine while we think about Jesus.’ There is rather more to it than that, I think! Increasingly lay people (and one suspects, the clergy too) came to Mass unprepared either spiritually (through prayer) and physically (through any sort of fast). The practise of Confession which had grown among Anglicans from the 19th century was dying out, and many presented themselves for Communion on a pretty haphazard basis. Expressions like ‘taking the bread and wine’ became commonplace as referring to receiving Holy Communion. With the discipline of the C of E collapsing as the state liberalised, and with sharing agreements with denominations who had no priesthood and no doctrine of the Real Presence or Eucharistic Sacrifice being voted through General Synod, it was hardly surprising that the Anglo-Catholics found it impossible to hold the line.

There were those who put it all down to the day the vicar abolished the non-communicating High Mass at 11, and introduced the ‘coffee-table’ in the nave. They ignored the simple fact that for nigh on a thousand years the laity had participated vigorously in the Mass and that a strong community discipline had co-existed with frequent and regular Communion. Indeed, it is difficult to see how the discipline of ‘ex-communication’ could be effective unless people went often to Communion!

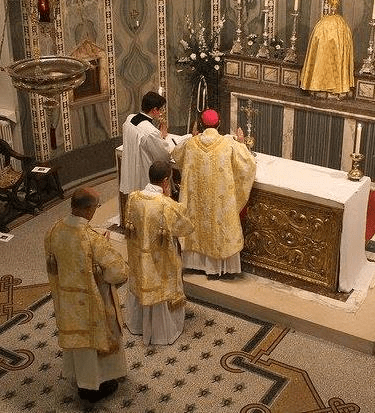

At its best – and it was often very good – the Anglo-Catholic Parish Mass was a wonderful expression of the worship of the Church. The church building may well have been sensitively re-ordered and the Blessed Sacrament given a prominent position on the old High Altar, while not confusing the celebration at the new liturgical Altar. The various ministries of the Mass were defined and ordered, with lay people, both men and women, reading and leading well-composed Intercessions. Preaching took on a new importance, and a well-crafted Homily was vital. The music was carefully chosen with continuing use of ‘strong’ hymns from the centuries; the Mass texts were usually sung by all the people, to the traditional music of Merbecke or (new words) Dom Gregory Murray. Teams of servers carried cross and candles and incense was almost always used on Sundays. The Offertory Procession became a focus of lay involvement and Communion was usually given from the bread and wine consecrated at that Mass. Increasingly baptisms were administered during the Parish Mass, with anointings and other blessings given. At the end of Mass many of the congregation would stay for further fellowship over refreshments. The Sunday worship in many Anglo-Catholic parishes was a worthy and devout offering, joyful, involving, instructive – and evangelising in the way that it spoke to occasionals and visitors and drew them into the life of the Parish Church.

In recent years this ‘norm’ of worship has fallen away in the C of E. I have already mentioned the unease of Evangelicals (too much attention paid to American Protestantism) with the Eucharist; for the liberal Establishment the panic over numbers, combined with an over-emphasis on ‘accessibility’ leading to some wild experiments and much rather empty and unsatisfying worship.

Now that mainstream Anglo-Catholicism has passed, in its earlier stage in the 1990’s, and more recently through the Ordinariate, back into Communion with the Holy See, it is my hope that we shall see the tradition of the Parish Mass becoming an accepted part of Catholic life. I believe it has the power to make Sunday worship come alive. Catholics from Africa and the Caribbean are often envious of their Pentecostal friends, and rather starved by their half-hour said Mass on Saturday evening. The Parish Mass tradition goes some way to meeting their needs. (And those who once worshipped in a black majority Anglo-Catholic congregation will know what a powerful and spiritual experience it often was).

Among Anglicans there used to be a saying, ‘The Lord’s Service, for the Lord’s People, on the Lord’s Day’: the Sunday Mass, celebrated by Catholic Christians, as their duty and their joy.

Over the years as an Anglican I waited for the publication of each new round of services. I took part in anguished discussions with fellow Anglo-Catholics as to how to make the best of these new rites. I read (and occasionally wrote) articles which tried to assess how much the Anglo-Catholics had got through the Synod, and what the Evangelicals had blocked or removed.

Over the years as an Anglican I waited for the publication of each new round of services. I took part in anguished discussions with fellow Anglo-Catholics as to how to make the best of these new rites. I read (and occasionally wrote) articles which tried to assess how much the Anglo-Catholics had got through the Synod, and what the Evangelicals had blocked or removed.