Derby Ordinariate Group

“The Ordinariate will grow – God willing.” When someone said this to me recently I reflected immediately that, of course, God wills it to grow! To put it round the other way, could God ever will his Church and his Kingdom to decline? So with God pouring his grace into the Ordinariate, as a movement within modern Christianity for renewal, unity and growth, what has the Ordinariate and the wider Catholic Church to do to ensure that God’s will is fulfilled? To be sure, God is not going to force his Church grow if it has become lazy and cynical; he surely expects us to read the signs of the times we live in, and to plan effectively to proclaim the Good News. He want us to live it out and to use every opportunity to share the Faith with those who know nothing of his love and his salvation.

As the Ordinariate has stabilised over the past two years no one pattern of group life has appeared: I have been able to locate at least four models. It is worth identifying these and thinking about the way they work (their dynamic). If there are others and if I am mistaken – especially about the groups of which I have no experience – then I hope to provoke others to show the contrary.

The ‘Once a month’ Group

An Ordinariate Group (former Anglicans, now Catholics, with their Priest-pastor) meets once a month on a Sunday. They meet in a Catholic Church where the Parish Priest is prepared to accommodate them, but at a time which fits in with the pre-existing ‘parish’ masses. This may mean 12.30 pm when most people are thinking about lunch or 4 pm when in winter it is rapidly getting dark. The Group members may well be travelling some distance (up to 50 miles in some rural areas). The nearest parallel as we try to think about this model is not the Congregation (the Group is too small and doesn’t meet every Sunday) nor yet the House Group (right size, most of them, but not frequent enough). It is rather the ‘special interest group’, like the Mother’s Union when we were in the C of E, or the Catenians in the Catholic Church. I know the Ordinariate is unlike both these groups in all sorts of ways – but the dynamic of the group (the way it functions) will be that of the monthly meeting of a special interest group. For a start, everyone coming will have been to Mass at their local Catholic Church on the three previous Sundays. They may well have started to get involved in their parish especially if they have made friends there. There may be discouraging noises from some in the Catholic community who ‘disapprove’ of the Ordinariate and want to see all former Anglicans ‘assimilate’ into the existing structures. What then, will make them go, once a month, to their Ordinariate Group?

Just going to Mass is not enough. It is early days yet for the Ordinariate Use, the special form of the Eucharist, and we cannot yet know whether it will become popular – and more important whether it has ‘pulling power.’ If it is just presented as an English version of the Extraordinary Form then one must ask: will people who like the old ways not just go to the ‘real thing’? No, much more care and thought is needed to present the Ordinariate Use as a genuine part of the Anglican Patrimony rather than a re-creation of Congress Anglo-Catholicism. If the group is only meeting once a month then some time needs to be given to the gathering, and resources and preparation are vital. The presentation of the Mass needs to be appropriate to the numbers attending (otherwise it can come over as rather pathetic) and should be followed by rather more than tea and biscuits. Let the group sit down for a meal together. (If you have to celebrate at 12.30 pm, you’ll all need it.) Each member of the group needs to take responsibility for another so that people do not lapse unnoticed. The continuing formation of the group in the Catholic Faith cannot be met by a 10 minute homily, and confidence is needed so that everyone can argue for the Christian and Catholic Faith with their neighbours and colleagues. So after the meal the pastor must teach – or he must arrange for good and enthusiastic teachers to join them for an hour. This is not a ‘discussion group’ let alone a ‘little talk’, though there needs to be time for question and answer and that vital business of chewing over what has been given. Evening Prayer (Evensong) said prayerfully or sung to simple plainchant is probably best to end the day – a day which has been worth coming to once a month.

Our sisters

The ‘Once-a-week Group’

This Ordinariate Group meets every Sunday i.e. for everyone in the Group it is their Sunday Mass. It is celebrated in a Catholic Parish Church with the agreement (and one supposes, the sympathy) of the Parish Priest and presided over by a priest of the Ordinariate. Its time will be by arrangement with the Parish, which in a busy one may mean 12.30 every week – hardly the best time to attract people? It may be that the Parish Priest is prepared to countenance one of the regular Masses (say Saturday night) going to the Ordinariate, but then he may not want them to use the Ordinariate Form of Mass (and this may be important to some groups, though not to others).

In this situation it is important to identify the relationship of the Group to the Parish. It may be ‘Separate Identity’, rather along the model of a Polish or Nigerian Group which meet to celebrate a Mass in their own language, and where the priest is a ‘visitor’. On the other hand it may be ‘Close Relationship’ where the Ordinariate priest works with the Parish Priest on a part-time basis and the Ordinariate members are involved in the life of the Parish. This is a mutually enriching arrangement, and could well mean that the Bishop in the future wishes to give the parish into the care of the Ordinariate. It is also possible that the Group, in the future, may become assimilated into the Catholic Parish, especially if their priest moves away.

The ‘Ordinariate Church’

In the early days of the Ordinariate it was believed that whole congregations of Catholic-minded Anglicans would wish to enter the full communion of the Church. It was thought that the Anglican authorities might be able to ‘release’ these church buildings from their parish system, allowing them to be quasi-independent Ordinariate churches situated in Catholic parishes, but with a status rather like a monastic conventual church. In the event nothing like this happened. Even with the ‘majority’ Ordinariate Groups, there was still a rump left behind: the Anglican dioceses made it quite clear that the one Christian group they would never share with was the Ordinariate; and the Catholic hierarchy for various reasons seemed not keen on any sharing arrangement. No group had the funds (or the confidence) to buy a redundant church (a Methodist chapel, for example). So in the UK we have little experience of how this model might function, but what of the theory? The Ordinariate Group and their Pastor will be large enough to function as a congregation, and financially viable. They will be able to find the skills, energy and enthusiasm both for maintenance and for mission. It is the priest who must hold the vision and be strong-willed enough to pursue it, while ready to listen and to enable the gifts of others. Such a vibrant congregation is likely to attract strong personalities. The priest must be able to help such people be part of the vision without dominating or insisting on their own interpretation of ‘how things should be done.’

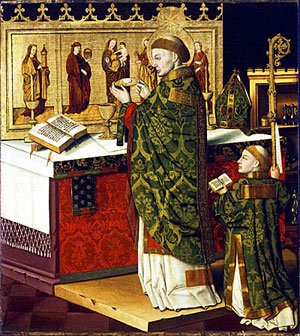

The Ordinariate Church will be strategically placed on good transport routes so that it can be a centre for individuals and for smaller groups. It will build up a library and catechetical centre both for the Ordiariate and for the wider Catholic Church. It will pioneer welcome and formation groups (‘Ordinariate Alpha!’) and work to keep open (from our side at least) the relationships with Anglo-Catholics still in the Church of England. This may not always be easy, as the ‘Christian Unity Movement’ has become stuck and complacent, and there are even some within our own Catholic Church who see the Ordinariate as a threat to this. The worship must be a model – not necessarily elaborate or expensive – in its noble simplicity of the English tradition of liturgy. It must avoid eccentricity and fussiness. The younger men, who sometimes have a hankering for a past they never knew, need good formation in the principles of liturgy. Preaching must be of the highest quality.

The ‘Ordinariate Parish’

Soon after joining the Ordinariate I wrote an article for the ‘Catholic Herald’ in which I suggested that Ordinariate Groups should become ‘church-planters’ – i.e. core groups of dedicated people sent into decaying Catholic parishes at the agreement of the local Bishop and the Ordinary, to revive, renew and build up such parishes. I still believe that this model is the most appropriate for the U.K situation. Those Catholic bishops who have taken the risk have not been disappointed. This model has not led to ‘assimilation’ as was feared. Even where the standard liturgy is not the Ordinariate Use but rather the Ordinary Form of the Roman Mass, nonetheless Catholic parishioners seem quite clear about the many things the Ordinariate brings, and they like them. What will happen to these parishes in the future? Some think that once they are going concerns, and the Ordinariate priest moves away, that the Diocesan Bishop will move the Ordinariate out. Does this happen with Religious Communities which run parishes? I think not. Some of our bishops may be cautious about the Ordinariate, but they are pragmatists. If their brother bishops give good reports of the Ordinariate, if the parishioners are happy, if the numbers are growing – then no Bishop is going to destroy this.

Each of these models functions differently, and for the foreseeable future we are going to have all of them. What is destructive is the failure to recognise the dynamic of the Group, to hanker after being something different, and to try to function and do things which are completely inappropriate for the size and situation of the group. Do very well what you are capable of; do not make a hash of what you clearly cannot manage!